Preface

Many professions require some form of programming. Accountants program

spreadsheets; musicians program synthesizers; authors program word

processors; and web designers program style sheets. When we wrote these

words for the first edition of the book (1995–2000), readers may have considered

them futuristic; by now, programming has become a required skill and

numerous outlets—

The typical course on programming teaches a “tinker until it works” approach. When it works, students exclaim “It works!” and move on. Sadly, this phrase is also the shortest lie in computing, and it has cost many people many hours of their lives. In contrast, this book focuses on habits of good programming, addressing both professional and vocational programmers.

By “good programming,” we mean an approach to the creation of software that relies on systematic thought, planning, and understanding from the very beginning, at every stage, and for every step. To emphasize the point, we speak of systematic program design and systematically designed programs. Critically, the latter articulates the rationale of the desired functionality. Good programming also satisfies an aesthetic sense of accomplishment; the elegance of a good program is comparable to time-tested poems or the black-and-white photographs of a bygone era. In short, programming differs from good programming like crayon sketches in a diner from oil paintings in a museum.

everyone can design programs

everyone can experience the satisfaction that comes with creative design.

program design—

but not programming— deserves the same role in a liberal-arts education as mathematics and language skills.

Systematic Program Design

A program interacts with people, dubbed users, and other programs, in which case we speak of server and client components. Hence any reasonably complete program consists of many building blocks: some deal with input, some create output, while some bridge the gap between those two. We choose to use functions as fundamental building blocks because everyone encounters functions in pre-algebra and because the simplest programs are just such functions. The key is to discover which functions are needed, how to connect them, and how to build them from basic ingredients.

In this context, “systematic program design” refers to a mix of two concepts: design recipes and iterative refinement.We drew inspiration from Michael Jackson’s method for creating COBOL programs plus conversations with Daniel Friedman on recursion, Robert Harper on type theory, and Daniel Jackson on software design. The design recipes are a creation of the authors, and here they enable the use of the latter.

From Problem Analysis to Data Definitions

Identify the information that must be represented and how it is represented in the chosen programming language. Formulate data definitions and illustrate them with examples.

Signature, Purpose Statement, Header

State what kind of data the desired function consumes and produces. Formulate a concise answer to the question what the function computes. Define a stub that lives up to the signature.

Functional Examples

Work through examples that illustrate the function’s purpose.

Function Template

Translate the data definitions into an outline of the function.

Function Definition

Fill in the gaps in the function template. Exploit the purpose statement and the examples.

Testing

Articulate the examples as tests and ensure that the function passes all. Doing so discovers mistakes. Tests also supplement examples in that they help others read and understand the definition when the need arises—

and it will arise for any serious program.

Design Recipes apply to both complete programs and individual functions. This book deals with just two recipes for complete programs: one for programs with a graphical user interface (GUI) and one for batch programs. In contrast, design recipes for functions come in a wide variety of flavors: for atomic forms of data such as numbers; for enumerations of different kinds of data; for data that compounds other data in a fixed manner; for finite but arbitrarily large data; and so on.

The function-level design recipes share a common design process. Figure 5 displays its six essential steps. The title of each step specifies the expected outcome(s); the “commands” suggest the key activities. Examples play a central role at almost every stage.Instructors Have students copy figure 5 on one side of an index card. When students are stuck, ask them to produce their card and point them to the step where they are stuck. For the chosen data representation in step 1, writing down examples proves how real-world information is encoded as data and how data is interpreted as information. Step 3 says that a problem-solver must work through concrete scenarios to gain an understanding of what the desired function is expected to compute for specific examples. This understanding is exploited in step 5, when it is time to define the function. Finally, step 6 demands that examples are turned into automated test code, which ensures that the function works properly for some cases. Running the function on real-world data may reveal other discrepancies between expectations and results.

Each step of the design process comes with pointed questions. For certain

steps—

The novelty of this approach is the creation of intermediate products for beginner-level programs. When a novice is stuck, an expert or an instructor can inspect the existing intermediate products. The inspection is likely to use the generic questions from the design process and thus drive the novice to correct himself or herself. And this self-empowering process is the key difference between programming and program design.

Iterative Refinement addresses the issue that problems are complex and multifaceted. Getting everything right at once is nearly impossible. Instead, computer scientists borrow iterative refinement from the physical sciences to tackle this design problem. In essence, iterative refinement recommends stripping away all inessential details at first and finding a solution for the remaining core problem. A refinement step adds in one of these omitted details and re-solves the expanded problem, using the existing solution as much as possible. A repetition, also called an iteration, of these refinement steps eventually leads to a complete solution.

In this sense, a programmer is a miniscientist. Scientists create approximate models for some idealized version of the world to make predictions about it. As long as the model’s predictions come true, everything is fine; when the predicted events differ from the actual ones, scientists revise their models to reduce the discrepancy. In a similar vein, when programmers are given a task, they create a first design, turn it into code, evaluate it with actual users, and iteratively refine the design until the program’s behavior closely matches the desired product.

This book introduces iterative refinement in two different ways. Since

designing via refinement becomes useful even when the design of programs becomes

complex, the book introduces the technique explicitly in the fourth part,

once the problems acquire a certain degree of difficulty. Furthermore, we

use iterative refinement to state increasingly complex variants of the

same problem over the course of the first three parts of the book. That

is, we pick a core problem, deal with it in one chapter, and then pose a

similar problem in a subsequent chapter—

DrRacket and the Teaching Languages

Learning to design programs calls for repeated hands-on practice. Just as nobody becomes a piano player without playing the piano, nobody becomes a program designer without creating actual programs and getting them to work properly. Hence, our book comes with a modicum of software support: a language in which to write down programs and a program development environment with which programs are edited like word documents and with which readers can run programs.

Many people we encounter tell us they wish they knew how to code and then ask which programming language they should learn. Given the press that some programming languages get, this question is not surprising. But it is also wholly inappropriate.Instructors For courses not aimed at beginners, it may be possible to use an off-the-shelf language with the design recipes. Learning to program in a currently fashionable programming language often sets up students for eventual failure. Fashion in this world is extremely short lived. A typical “quick programming in X” book or course fails to teach principles that transfer to the next fashion language. Worse, the language itself often distracts from the acquisition of transferable skills, at the level of both expressing solutions and dealing with programming mistakes.

In contrast, learning to design programs is primarily about the study of principles and the acquisition of transferable skills. The ideal programming language must support these two goals, but no off-the-shelf industrial language does so. The crucial problem is that beginners make mistakes before they know much of the language, yet programming languages always diagnose these errors as if the programmer already knew the whole language. As a result, diagnosis reports often stump beginners.

Our solution is to start with our own tailor-made teaching language, dubbed “Beginning Student Language” or BSL. The language is essentially the “foreign” language that students acquire in pre-algebra courses. It includes notation for function definitions, function applications, and conditional expressions. Also, expressions can beInstructors You may wish to explain that BSL is pre-algebra with additional forms of data and a host of pre-defined functions on those. nested. This language is thus so small that an error diagnosis in terms of the whole language is still accessible to readers with nothing but pre-algebra under their belt.

A student who has mastered the structural design principles can then move on to “Intermediate Student Language” and other advanced dialects, collectively dubbed *SL. The book uses these dialects to teach design principles of abstraction and general recursion. We firmly believe that using such a series of teaching languages provides readers with a superior preparation for creating programs for the wide spectrum of professional programming languages (JavaScript, Python, Ruby, Java, and others).

Note The teaching languages are implemented in Racket, a programming language we built for building programming languages. Racket has escaped from the lab into the real world, and it is a programming vehicle of choice in a variety of settings, from gaming to the control of telescope arrays. Although the teaching languages borrow elements from the Racket language, this book does not teach Racket. Then again, a student who has completed this book can easily move on to Racket. End

When it comes to programming environments, we face an equally bad choice as the one for languages. A programming environment for professionals is analogous to the cockpit of a jumbo jet. It has numerous controls and displays, overwhelming anyone who first launches such a software application. Novice programmers need the equivalent of a two-seat, single-engine propeller aircraft with which they can practice basic skills. We have therefore created DrRacket, a programming environment for novices.

DrRacket supports highly playful, feedback-oriented learning with just two simple interactive panes: a definitions area, which contains function definitions, and an interactions area, which allows a programmer to ask for the evaluation of expressions that may refer to the definitions. In this context, it is as easy to explore “what if” scenarios as in a spreadsheet application. Experimentation can start on first contact, using conventional calculator-style examples and quickly proceeding to calculations with images, words, and other forms of data.

An interactive program development environment such as DrRacket simplifies the learning process in two ways. First, it enables novice programmers to manipulate data directly. Because no facilities for reading input information from files or devices are needed, novices don’t need to spend valuable time on figuring out how these work. Second, the arrangement strictly separates data and data manipulation from input and output of information from the “real world.” Nowadays this separation is considered so fundamental to the systematic design of software that it has its own name: model-view-controller architecture. By working in DrRacket, new programmers are exposed to this fundamental software engineering idea in a natural way from the get-go.

Skills that Transfer

The skills acquired from learning to design programs systematically transfer in two directions. Naturally, they apply to programming in general as well as to programming spreadsheets, synthesizers, style sheets, and even word processors. Our observations suggest that the design process from figure 5 carries over to almost any programming language, and it works for 10-line programs as well as for 10,000-line programs. It takes some reflection to adopt the design process across the spectrum of languages and scale of programming problems; but once the process becomes second nature, its use pays off in many ways.

Learning to design programs also means acquiring two kinds of universally useful skills. Program design certainly teaches the same analytical skills as mathematics, especially (pre)algebra and geometry. But, unlike mathematics, working with programs is an active approach to learning. Creating software provides immediate feedback and thus leads to exploration, experimentation, and self-evaluation. The results tend to be interactive products, an approach that vastly increases the sense of accomplishment when compared to drill exercises in textbooks.

In addition to enhancing a student’s mathematical skills, program design teaches analytical reading and writing skills. Even the smallest design tasks are formulated as word problems. Without solid reading and comprehension skills, it is impossible to design programs that solve a reasonably complex problem. Conversely, program design methods force a creator to articulate his or her thoughts in proper and precise language. Indeed, if students truly absorb the design recipe, they enhance their articulation skills more than anything else.

analyze a problem statement, typically stated as a word problem;

extract and express its essence, abstractly;

illustrate the essence with examples;

make outlines and plans based on this analysis;

evaluate results with respect to expected outcomes; and

revise the product in light of failed checks and tests.

Each step requires analysis, precision, description, focus, and attention

to details. Any experienced entrepreneur, engineer, journalist,

lawyer, scientist, or any other professional can explain how many of

these skills are necessary for his or her daily work. Practicing program

design—

Similarly, refining designs is not restricted to computer science and program creation. Architects, composers, writers, and other professionals do it, too. They start with ideas in their head and somehow articulate their essence. They refine these ideas on paper until their product reflects their mental image as much as possible. As they bring their ideas to paper, they employ skills analogous to fully absorbed design recipes: drawing, writing, or piano playing to express certain style elements of a building, describe a person’s character, or formulate portions of a melody. What makes them productive with an iterative development process is that they have absorbed their basic design recipes and learned how to choose which one to use for the current situation.

This Book and Its Parts

The purpose of this book is to introduce readers without prior experience

to the systematic design of programs. In tandem, it presents a

symbolic view of computation, a method that explains how the

application of a program to data works. Roughly speaking, this method

generalizes what students learn in elementary school arithmetic and middle

school algebra. But have no fear. DrRacket comes with a mechanism—

The book consists of six parts separated by five intermezzos and is bookended by a Prologue and an Epilogue. While the major parts focus on program design, the intermezzos introduce supplementary concepts concerning programming mechanics and computing.

Fixed-Size Data explains the most fundamental concepts of systematic design using simple examples. The central idea is that designers typically have a rough idea of what data the program is supposed to consume and produce. A systematic approach to design must therefore extract as many hints as possible from the description of the data that flows into and out of a program. To keep things simple, this part starts with atomic data—

numbers, images, and so on— and then gradually introduces new ways of describing data: intervals, enumerations, itemizations, structures, and combinations of these. Intermezzo 1: Beginning Student Language describes the teaching language in complete detail: its vocabulary, its grammar, and its meaning. Computer scientists refer to these as syntax and semantics. Program designers use this model of computation to predict what their creations compute when run or to analyze error diagnostics.

Arbitrarily Large Data extends Fixed-Size Data with the means to describe the most interesting and useful forms of data: arbitrarily large compound data. While a programmer may nest the kinds of data from Fixed-Size Data to represent information, the nesting is always of a fixed depth and breadth. This part shows how a subtle generalization gets us from there to data of arbitrary size. The focus then switches to the systematic design of programs that process this kind of data.

Intermezzo 2: Quote, Unquote introduces a concise and powerful notation for writing down large pieces of data: quotation and anti-quotation.

Abstraction acknowledges that many of the functions from Arbitrarily Large Data look alike. No programming language should force programmers to create pieces of code that are so similar to each other. Conversely, every good programming language comes with ways to eliminate such similarities. Computer scientists call both the step of eliminating similarities and its result abstraction, and they know that abstractions greatly increase a programmer’s productivity. Hence, this part introduces design recipes for creating and using abstractions.

Intermezzo 3: Scope and Abstraction plays two roles. On the one hand, it injects the concept of lexical scope, the idea that a programming language ties every occurrence of a name to a definition that a programmer can find with an inspection of the code. On the other hand, it explains a library with additional mechanisms for abstraction, including so-called for loops.

Intertwined Data generalizes Arbitrarily Large Data and explicitly introduces the idea of iterative refinement into the catalog of design concepts.

Intermezzo 4: The Nature of Numbers explains and illustrates why decimal numbers work in such strange ways in all programming languages. Every budding programmer ought to know these basic facts.

Generative Recursion adds a new design principle. While structural design and abstraction suffice for most problems that programmers encounter, they occasionally lead to insufficiently “performant” programs. That is, structurally designed programs might need too much time or energy to compute the desired answers. Computer scientists therefore replace structurally designed programs with programs that benefit from ad hoc insights into the problem domain. This part of the book shows how to design a large class of just such programs.

Intermezzo 5: The Cost of Computation uses examples from Generative Recursion to illustrate how computer scientists think about performance.

Accumulators adds one final trick to the toolbox of designers: accumulators. Roughly speaking, an accumulator adds “memory” to a function. The addition of memory greatly improves the performance of structurally designed functions from the first four parts of the book. For the ad hoc programs from Generative Recursion, accumulators can make the difference between finding an answer and never finding one.

Independent readers ought to work through the entire book, from the first page to the last. We say “work” because we really mean that a reader ought to solve all exercises or at least know how to solve them.

Similarly, instructors ought to cover as many elements as possible, starting from the Prologue all the way through the Epilogue. Our teaching experience suggests that this is doable. Typically, we organize our courses so that our readers create a sizable and entertaining program over the course of the semester. We understand, however, that some circumstances call for significant cuts and that some instructors’ tastes call for slightly different ways to use the book.

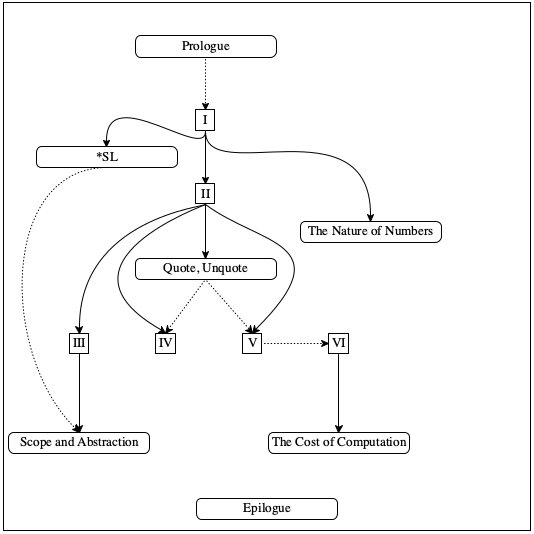

Figure 6 is a navigation chart for those who wish to pick and choose from the elements of the book. The figure is a dependency graph. A solid arrow from one element to another suggests a mandatory ordering; for example, Part II requires an understanding of Part I. In contrast, a dotted arrow is mostly a suggestion; for example, understanding the Prologue is unnecessary to get through the rest of the book.

A high school instructor may want to cover (as much as possible of) parts I and II, including a small project such as a game.

A college instructor in a quarter system may wish to focus on Fixed-Size Data, Arbitrarily Large Data, Abstraction, and Generative Recursion, plus the intermezzos on *SL and scope.

A college instructor in a semester system may prefer to discuss performance trade-offs in designs as early as possible. In this case, it is best to cover Fixed-Size Data and Arbitrarily Large Data and then the accumulator material from Accumulators that does not depend on Generative Recursion. At that point, it is possible to discuss Intermezzo 5: The Cost of Computation and to study the rest of the book from this angle.

Iteration of Sample Topics The book revisits certain exercise and sample topics time and again. For example, virtual pets are found all over Fixed-Size Data and even show up in Arbitrarily Large Data. Similarly, both Fixed-Size Data and Arbitrarily Large Data cover alternative approaches to implementing an interactive text editor. Graphs appear in Generative Recursion and immediately again in Accumulators. The purpose of these iterations is to motivate iterative refinement and to introduce it through the backdoor. We urge instructors to assign these themed sequences of exercises or to create their own such sequences.

The Differences

It explicitly acknowledges the difference between designing a whole program and the functions that make up a program. Specifically, this edition focuses on two kinds of programs: event-driven (mostly GUI, but also networking) programs and batch programs.

The design of a program proceeds in a top-down planning phase followed by a bottom-up construction phase. We explicitly show how the interface to libraries dictates the shape of certain program elements. In particular, the very first phase of a program design yields a wish list of functions. While the concept of a wish list exists in the first edition, this second edition treats it as an explicit design element.

Fulfilling an entry from the wish list relies on the function design recipe, which is the subject of the six major parts.

A key element of structural design is the definition of functions that compose others. This design-by-composition is especially useful for the world of batch programs. Like generative recursion,We thank Kathi Fisler for calling our attention to this point. it requires a eureka!, specifically a recognition that the creation of intermediate data by one function and processing this intermediate result by a second function simplifies the overall design. This approach also needs a wish list, but formulating these wishes calls for an insightful development of an intermediate data definition. This edition of the book weaves in a number of explicit exercises on design by composition.

While testing has always been a part of our design philosophy, the teaching languages and DrRacket started supporting it properly only in 2002, just after we had released the first edition. This new edition heavily relies on this testing support.

This edition of the book drops the design of imperative programs. The old chapters remain available on-line. An adaptation of this material will appear in the second volume of this series, How to Design Components.

The book’s examples and exercises employ new teachpacks. The preferred style is to link in these libraries via require, but it is still possible to add teachpacks via a menu in DrRacket.

- Finally, this second edition differs from the first in a few aspects of terminology and notation:The last three differences greatly improve quotation for lists.

Acknowledgments from the First Edition

Four people deserve special thanks: Robert “Corky” Cartwright, who co-developed a predecessor of Rice University’s introductory course with the first author; Daniel P. Friedman, for asking the first author to rewrite The Little LISPer (also MIT Press) in 1984, because it started this project; John Clements, who designed, implemented, and maintains DrRacket’s stepper; and Paul Steckler, who faithfully supported the team with contributions to our suite of programming tools.

The development of the book benefited from many other friends and colleagues who used it in courses and/or gave detailed comments on early drafts. We are grateful to them for their help and patience: Ian Barland, John Clements, Bruce Duba, Mike Ernst, Kathi Fisler, Daniel P. Friedman, John Greiner, Géraldine Morin, John Stone, and Valdemar Tamez.

A dozen generations of Comp 210 students at Rice used early drafts of the text and contributed improvements in various ways. In addition, numerous attendees of our TeachScheme! workshops used early drafts in their classrooms. Many sent in comments and suggestions. As representative of these we mention the following active contributors: Ms. Barbara Adler, Dr. Stephen Bloch, Ms. Karen Buras, Mr. Jack Clay, Dr. Richard Clemens, Mr. Kyle Gillette, Mr. Marvin Hernandez, Mr. Michael Hunt, Ms. Karen North, Mr. Jamie Raymond, and Mr. Robert Reid. Christopher Felleisen patiently worked through the first few parts of the book with his father and provided direct insight into the views of a young student. Hrvoje Blazevic (sailing, at the time, as Master of the LPG/C Harriette), Joe Zachary (University of Utah), and Daniel P. Friedman (Indiana University) discovered numerous typos in the first printing, which we have now fixed. Thank you to everyone.

Finally, Matthias expresses his gratitude to Helga for her many years of patience and for creating a home for an absent-minded husband and father. Robby is grateful to Hsing-Huei Huang for her support and encouragement; without her, he would not have gotten anything done. Matthew thanks Wen Yuan for her constant support and enduring music. Shriram is indebted to Kathi Fisler for support, patience and puns, and for her participation in this project.

Acknowledgments

As in 2001, we are grateful to John Clements for designing, validating, implementing, and maintaining DrRacket’s algebraic stepper. He has done so for nearly 20 years now, and the stepper has become an indispensable tool of explanation and instruction.

Over the past few years, several colleagues have commented on the various drafts and suggested improvements. We gratefully acknowledge the thoughtful conversations and exchanges with these individuals:

Kathi Fisler (WPI and Brown University), Gregor Kiczales (University of British Columbia), Prabhakar Ragde (University of Waterloo), and Norman Ramsey (Tufts University).

Guillaume Marceau, working with Kathi Fisler and Shriram, spent many months studying and improving the error messages in DrRacket. We are grateful for his amazing work.

Celeste Hollenbeck is the most amazing reader ever. She never tired of pushing back until she understood the prose. She never stopped until a section supported its thesis, its organization matched, and its sentences connected. Thank you very much for your incredible efforts.

We also thank the following: Ennas Abdussalam, Mark Aldrich, Mehmet Akif Akkus, Anisa Anuar, Franco Barbeite, Saad Bashir, Aaron Bauman, Suzanne Becker, Michael Bausch, Steven Belknap, Stephen Bloch, Elijah Botkin, Joseph Bogart William Brown, Tomas Cabrera, Xuyuqun C, Colin Caine, Anthony Carrico, Rodolfo Carvalho, Estevo Castro, Maria Chacon, Stephen Chang, David Chatman, Burleigh Chariton, Tung Cheng, Nelson Chiu, Jack Clay, Richard Cleis, John Clements, Scott Crymble, Pierce Darragh, Jonas Decraecker, Qu Dongfang, Mark Engelberg, Thomas Evans, Andrew Fallows, Jiankun Fan, Christopher Felleisen, Sebastian Felleisen, Vladimir Gajić, Xin Gao, Adrian German, Jack Gitelson, Kyle Gillette, Scott Greene, Ben Greenman, Ryan Golbeck, Josh Grams, Grigorios, Jane Griscti, Alberto E. F. Guerrero, Tyler Hammond, Nan Halberg, Li Junsong, Nadeem Abdul Hamid, Jeremy Hanlon, Tony Henk, Craig Holbrook, Connor Hetzler, Benjamin Hosseinzahl, Wayne Iba, John Jackaman, Jordan Johnson, Blake Johnson, Erwin Junge, Marc Kaufmann, Cole Kendrick, Gregor Kiczales, Eugene Kohlbecker, Jaroslaw Kolosowski, Caitlin Kramer, Roman Kunin, Jackson Lawler, Devon LePage, Ben Lerner, Shicheng Li, Chen Lj, Ed Maphis, YuSheng Mei, Andres Meza, Saad Mhmood, Elena Machkasova, Jay Martin, Alexander Martinez, Yury Mashika, Jay McCarthy, James McDonell, Mike McHugh, Wade McReynolds, David Moses, Ann E. Moskol, Scott Newson, , Štěpán Němec, Paul Ojanen, Prof. Robert Ordóñez, Laurent Orseau, Klaus Ostermann, Alanna Pasco, Sinan Pehlivanoglu, Eric Parker, David Porter, Nick Pleatsikas, Prathyush Pramod, Alok Rai, Norman Ramsey, Krishnan Ravikumar, Jacob Rubin, Ilnar Salimzianov, Luis Sanjuán, Brian Schack, Ryan “Havvy” Scheel, Lisa Scheuing, Willi Schiegel, Vinit Shah, Nick Shelley, Edward Shen, Tubo Shi, Hyeyoung Shin, Atharva Shukla, Matthew Singer, Michael Siegel, Stephen Siegel, Milton Silva, Kartik Singhal, Joe Snikeris, Marc Smith, Matthijs Smith, Dave Smylie, Vincent St-Amour, Reed Stevens, William Stevenson, Kevin Sullivan, Asumu Takikawa, Éric Tanter, Sam Tobin-Hochstadt, Thanos Tsouanas, Aaron Tsay, Mariska Twaalfhoven, Bor Gonzalez Usach, Ricardo Ruy Valle-mena, Manuel del Valle, David Van Horn, Nick Vaughn, Simeon Veldstra, Andre Venter, Jan Vitek, Marco Villotta, Mitch Wand, Yuxu (Ewen) Wang, Michael Wijaya, G. Clifford Williams, Ewan Whittaker-Walker, Julia Wlochowski, Roelof Wobben, J.T. Wright, Mardin Yadegar, Huang Yichao, Yuwang Yin, Andrew Zipperer, Ari Zvi for comments on drafts of this second edition.

The HTML layout at htdp.org is the work of Matthew Butterick, who created these styles for our on-line documentation.

Finally, we are grateful to Ada Brunstein and Marie Lufkin Lee, our editors at MIT Press, who gave us permission to develop this second edition of How to Design Programs on the web. We also thank MIT’s Christine Bridget Savage and John Hoey from Westchester Publishing Services for managing the final production process. John Donohue, Jennifer Robertson, and Mark Woodworth did a wonderful job of copy editing the manuscript.